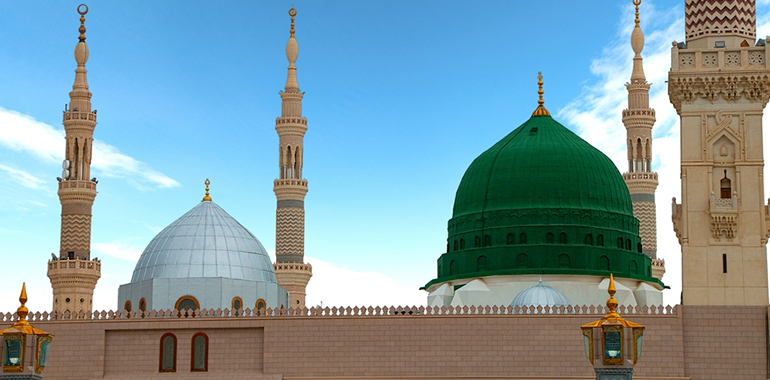

p>Hajj, one of the five fundamental pillars of the religion, is an act of worship deeply imbued with symbols. As a form of worship that enables our spiritual and physical encounter with the Ka‘bah, toward which we turn at least five times a day, Hajj is a divine journey that draws the servant closer to his Lord. Hajj, imbued with such profound meanings, begins with ihram. Just as prayer begins with the proclamation of takbir, so too does the pilgrim begin Hajj by entering into ihram. With the two simple white garments we wear, we silently express to Allah the Almighty our desire to return to the purity and innocence of the day our mothers brought us into this world. We weep and earnestly plead with our Lord for our book of deeds to be as pure and spotless as the ihrams upon us. The clothing that earns us esteem in society, the makeup we apply to look more attractive, the perfumes we wear to smell pleasant—none of these have a place while in ihram. We are no longer superiors or subordinates, neither business people nor laborers, neither wealthy nor poor. We are nothing but servants created by Allah. We seek only one rank, the highest of all ranks: the station of servitude to Allah. The attention we have shown to our bodies until now is sufficient, and it is now time to nourish and mature our souls. That is why our hair is unkempt, why we go barefoot, and why we abandon the garments we usually wear. In truth, through this disheveled state, we confess our weakness before our Lord and, in essence, plead, “My Lord, I am helpless, and You are the Most Exalted; I am powerless, and You are the All-Powerful; I am lowly, and You are the Almighty. Without You by my side, I am alone—I am nothing. Do not leave me without You, without Your help!” With the ihram donned and the talbiyah constantly upon his lips, the pilgrim declares his response to the call of his Lord, just as a soldier presents himself to his commander with the words, “At your command, sir”. In doing so, he affirms his readiness to fulfill all of Allah’s commands from that moment onward. Moreover, through the miqat boundaries—limits that must not be crossed without entering into ihram—the pilgrim comes to realize that Allah has established specific boundaries (hududullah) in every aspect of life and that observing these boundaries is not optional but an obligation. At last, the longing ends, and the pilgrim stands face to face with the Ka‘bah. Now, he too is in the very place where the Prophet Adam, the Prophet Ibrahim, the Prophet Isma‘il, and our beloved Prophet Muhammad (saw) once set foot. In remembrance of their legacy, he joins the glorification of the universe. Just as everything in existence, from the electrons, protons, and neutrons within atoms to the vast galaxies, moves in harmony, he too begins to circle from left to right. By circumambulating in a counterclockwise direction—as if turning back the clock—he seeks to return to his origin. With every step, every tawaf, he yearns to be as pure as the day he was born, cleansed of all sin. By greeting the Hajar al-Aswad, the pilgrim renews his covenant of servitude and begins the tawaf. With each circuit, it is as though he proclaims: “My Lord! Just as I revolve around this House of Yours today, spinning like a moth drawn to light, I will likewise revolve around Your commands and prohibitions for the rest of my life. I will do what You have commanded and refrain from what You have forbidden.” With the sa‘y performed after the tawaf, the memory of Hajar is honored. One comes to realize that if one truly wishes to be a sincere servant, then, like her, one must possess unwavering tawakkul, never lose hope in Allah even for a moment, and remember Him in both moments of joy and times of hardship alike, never allowing His remembrance to leave the mind or heart. The time has now come for ‘Arafat’. Arafat is a moment of standing, of judgment, and purification, a rehearsal for the Day of Resurrection. Clothed in his shroud-like ihram garments before he has even died, the servant stands in the presence of the Supreme Judge, as though in a courtroom, accounting for his past deeds, expressing his remorse, and ultimately beginning to be cleansed through the forgiveness of his sins. Having been cleansed of his sins on the plain of ‘Arafat, the servant now departs to confront and do battle with his greatest enemy, Satan. In Mina, just as his forefather, the Prophet Ibrahim, did, he initiates the battle at three distinct points and begins the ritual of stoning Satan. The pilgrim is well aware that he is not striking a physical form of Satan. What he is truly casting stones at are the sins he committed by following Satan and the devilish desires and inclinations that took root within him. Each stone is a declaration: “Enough!” It is a rejection of Satan’s sway, a determined break from his grip, and a firm affirmation that Satan is the foremost enemy to be resisted. A Muslim who has fulfilled the duty of stoning Satan then offers the sacrifice (qurbani) as a sign of his commitment to uphold the promises he has made until that point. This sacrifice, so to speak, serves as a signature placed beneath the covenant of servitude made with Allah. Now entitled to bear the title of pilgrim, the Muslim—cleansed of sins— performs the act of shaving the head, a symbol of rebirth. The old chapters have been closed. A brandnew life lies ahead. In this new life, he will refrain from anything that does not earn the pleasure of his Lord, and he will remain faithful to the promises he has made. By shaving his head, the pilgrim also offers, in a sense, a part of his own body as a sacrifice, leaving behind a personal trace in the sacred precinct of the Haram. Thus, every pilgrim who performs the Hajj with this spirit and determination will, by the grace of Allah, be granted the glad tidings expressed in the hadith mentioned above (inshallah): “…he will come out as sinless as a newborn child ( Just delivered by his mother).”

THE JOURNEY TO FITRAH: HAJJ